You can also listen to this article in the following audio:

Over time, Independence Day commemorations have undergone significant changes, always capturing the unique essence of the local culture and leaving a mark of the distinctive character imprinted by political and social events in our nation.

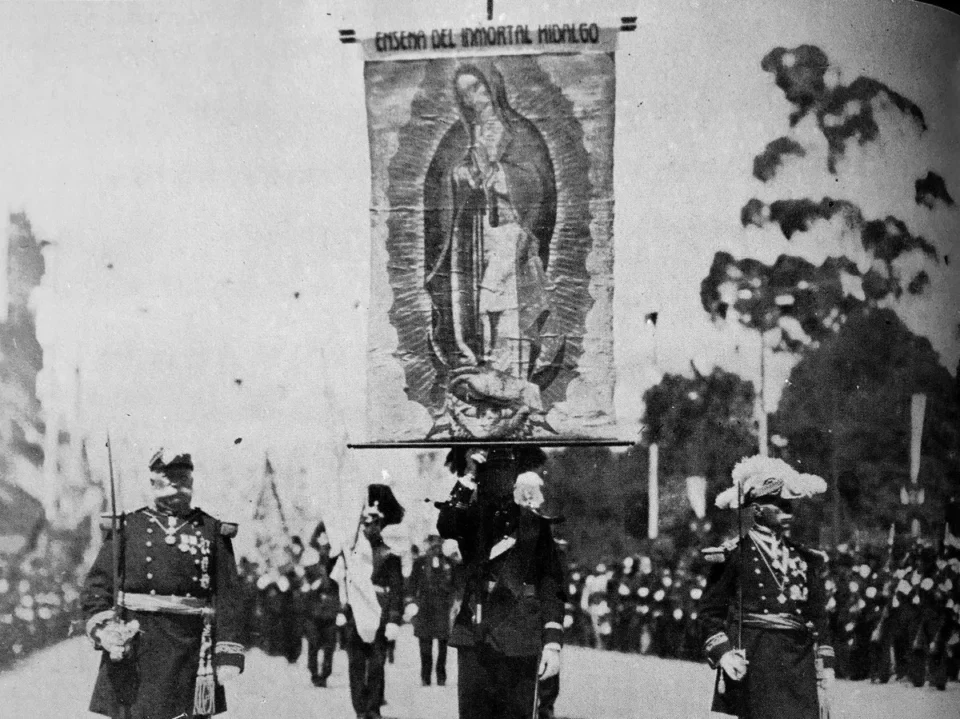

A few years ago, the patriotic festivities began to take place in the Historic Center, following the same tradition that still lasts. This change coincided with Porfirio Díaz’s order to move the bell that the priest Hidalgo had rung in the church of Dolores to the main balcony of the National Palace. Since 1896, the bell has rung every year in the hands of the president in office, marking the beginning of the festivities.

These events of grandeur and rejoicing contrast sharply with the first celebration that took place on September 16, 1812 in Huichapan, a town in Hidalgo. On this occasion, Ignacio López Rayón was responsible for the organization, as reported by Emmanuel Carballo in his work “Las fiestas patrias en la narrativa nacional”, the source to which we have resorted for this story.

September 16, declared as a day of remembrance

It was in 1824 when Mexico’s Constituent Congress made September 16 official as the day commemorating the beginning of the struggle for independence. In the following year, the authorities of the capital issued a proclamation urging citizens to decorate and illuminate their homes with patriotic symbols.

At the same time, President Guadalupe Victoria received allusive congratulations from diplomats and civil and ecclesiastical leaders. That year marked the debut of a parade through the streets of Mexico City, celebrating the patriotic spirit.

In the decades that followed, the festivities did not escape the vicissitudes of the nation. Miguel Hidalgo’s harangue (“¡Mueran los gachupines!”) inspired many Mexicans, especially after the failed attempt at Spanish reconquest in 1829.

However, in 1847, due to the presence of General Scott’s forces, the mood in the capital was not for celebrations, and that year’s festivities had to be cancelled.

Celebration of September 16 in the Porfirian era

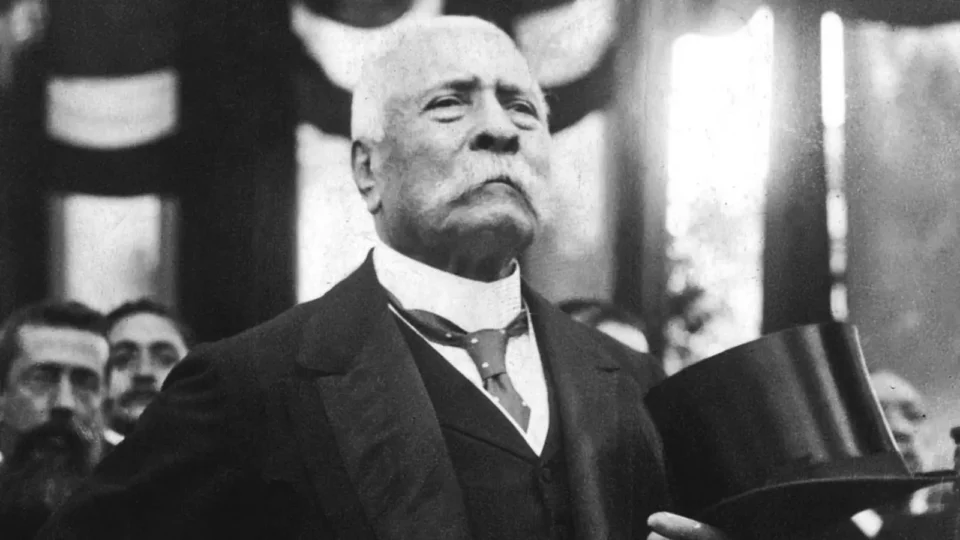

The history of patriotic celebrations also recorded turbulent moments, such as the incident during the military parade of September 16, 1897. In that parade, while passing through the Alameda, a man under the influence of alcohol rushed from the crowd to attack Porfirio Díaz. Although the attacker, named Arnulfo Arollo, was immediately arrested, the president continued on his way as if nothing had happened.

That night, a mob assaulted the police station where Arollo was detained, resulting in his lynching. This dramatic story is recreated by novelist Álvaro Uribe in “Expediente del atentado”, which was later made into a film version directed by Jorge Fons.

The commemorative festivities of the centennial of the beginning of the Independence War could not mask the social unrest that finally unleashed in 1910, as was meticulously recorded in his diaries by the Mexican novelist and playwright Federico Gamboa.

In his accounts, Gamboa described how from one of the balconies of the National Palace he observed the tumultuous entrance of Maderista demonstrators into the Zócalo. These demonstrators carried a banner bearing the image of the future “Apostle of Democracy”.

At that moment, the author of the novel “Santa”, who at the time was a Porfirian official, resorted to cynicism when he explained to a perplexed foreign diplomat standing next to him that the clamors in the unfamiliar local language were actually acclamations to President Porfirio Diaz, whose young, bearded image the demonstrators were holding up.

We hope you liked this article, you can follow us on our social networks to be aware of new material that we upload, we hope to see you here soon.